A Terraformd Homelab

Overview

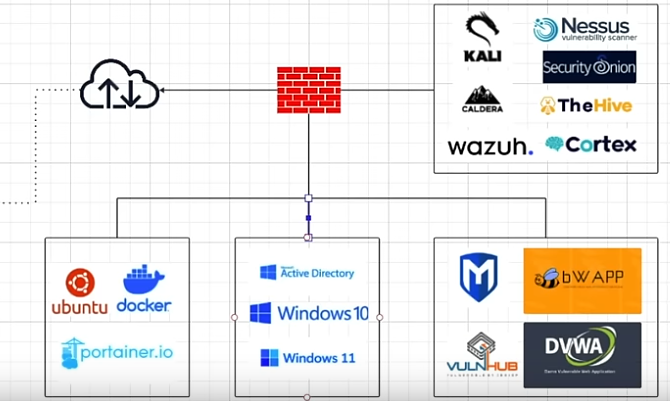

I have been humbly trying to learn Terraform locally because provisioning cloud resources is a costly endeavour. And trying to learn a tool that is primarily for cloud usage on a local environment definitely incurs some headaches. So my goal trying to broaden my understanding of all modern I.T infrastructure and my pursuit of cybersecurity was to build a cybersecurity homelab, something along the lines of

Although, I’ll just be starting off with 3 VLANS, a wazuh-server, agent and a firewall. The firewall being VyOS (if you have ever tried to automate pfSense, you understand why) This was a delightful goal and doesn’t seem that hard to setup. Because it’s just like one sentence. But as with most things in I.T you learn very quickly that one sentence can become a day or more (much more) of labor and education in things you didn’t expect to be educated on. The list includes:

- Networking

- Interfaces

- DNS

- DHCP

- Firewalls

- Routing

- Terraform

- It’s concept of ownership and state management

- Accidental deletion of images because of how it manages state

- Modular Deployments

- Cloud Images

- Cloud-init

And that’s just a small sample of high-level stuff I had to deal with. The completed and potential ongoings are here: Homelab

VyOS

Enter VyOS This is an open source firewall, much like pfSense. However, it’s far easier to configure programatically than pfSense which is why I chose it. Unfortunately, it’s easier to automate, but I still couldn’t find an image that had cloud-init preinstalled and I had even tried building my own inside a docker container, but upon booting it failed. So I had to self-install and then turn it into a golden image where the first interface is activated and ssh is enabled. This wasn’t too terrible.

Learning you can connect to VM’s in console without a graphical interface and have it directly in the console was also neat. And you can use <C-A> X to exit

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

qemu-system-x86_64 \

-name headless-vyos \

-m 2048 \

-smp 2 \

-cdrom vyos.iso \

-drive file=vyos_disk.qcow2,format=qcow2 \

-boot order=d \

-nographic \

-serial mon:stdio \

-net nic -net user,hostfwd=tcp::2222-:22

1

2

3

4

5

# On the VyOS Image

configure

set interfacees ethernet eth0 address dhcp

set interfacees ethernet eth0 description 'ExternalNet'

set service ssh port '22'

So now we can start utilizing this inside terraform, which I intitially thought we could just run the iso and boot it like that within it. You could. However it’s not practical for a deployment to install your ISO, which is why I was on the hunt for cloudimages and it’s why cloud companies have a plethora of images like that. It’s much more seamless.

Terraform Overview

So now we’re playing with Terraform. Since I’m using qemu that made me have to use libvirtd as the terraform “provider” Terraform is a very interesting tool and comes with it’s own configuration language called Hashicorp Configuration Language (HCL). At first, I disliked having to learn yet another markup language, but honestly I started growing fond of it after using it, because it seems far more readable than even yaml. I obviously didn’t start of thinking that, I hated it because I thought I had to specify everything in blocks and then you get a lot of repetition. I learned rather quickly though that Mitchell Hasimoto is pretty respected for a reason.

So Terraform works with these things called “providers” which is a link to an API interface, this is what allows it to integrate into various cloud environments whether that be AWS, Google Cloud, or in my case libvirtd. So through the API you get “resources” and can define your networks, network interfaces, image pools and everything.

So we start off with our image pool, and our networks.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

terraform {

required_providers {

libvirt = {

source = "dmacvicar/libvirt"

version = "~> 0.8.3"

}

}

}

# provider "libvirt" {

# uri = "qemu:///system"

# }

#### IMAGES ####

variable "wan_subnet" {}

variable "lan_subnet" {}

variable "local_url" {

description = "Base Localhost url for downloading images"

type = string

default = "http://localhost:8000"

}

variable "pool_name" {

description = "Name of images pool"

type = string

default = "tmp"

}

locals {

base_images = {

vyos = "vyos.qcow2"

# fedora = "fedora.qcow2"

# ubuntu = "ubuntu.qcow2"

}

vlan_ids = {

fedora = 10

ubuntu = 20

windows = 30

}

pool_path = "/opt/homelab_images"

}

resource "libvirt_pool" "tmp_images" {

name = var.pool_name

type = "dir"

target {

path = local.pool_path

}

}

# Dynamically create volume resources

# Outputs as a map "base_img[key]"

resource "libvirt_volume" "base_img" {

for_each = local.base_images

name = each.value

source = "${var.local_url}/${each.value}"

pool = var.pool_name

format = "qcow2"

depends_on = [libvirt_pool.tmp_images]

}

#### NETWORKS #####

resource "libvirt_network" "homelab_net" {

name = "homelab"

mode = "nat"

domain = "homelab.local"

addresses = [var.wan_subnet]

dhcp {

enabled = true

}

dns {

enabled = true

}

}

resource "libvirt_network" "homelab_lan" {

name = "homelab_lan"

mode = "bridge"

bridge = "br_lan"

}

This sets up two virtual networks: homelab_net (for NAT), homelab_lan (the Bridge for the rest of the VMs) And sets up an image pool for terraform to grab images from, so we would have to setup a webserver in our images directory. So we’re kind of emulating a cloud environment in a local setting. So it will pull the image and provision it.

The next step is booting VyOS, because we set up our basic infrastructure, but now we need to actually pull our VMs and set them up.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

terraform {

required_providers {

libvirt = {

source = "dmacvicar/libvirt"

version = "~> 0.8.3"

}

}

}

# provider "libvirt" {

# uri = "qemu:///system"

# }

# Define input variables

variable "lan_id" {}

variable "wan_id" {}

variable "image_id" {}

variable "pool_name" {}

variable "wan_address" {}

variable "lan_address" {}

variable "static_ip" {}

# variable "vm_name" {}

# variable "vm_memory" {}

# variable "vm_vcpu" {}

variable "ssh_pubkey_path" {}

variable "ssh_keytype" { default = "ssh-ed25519" }

resource "random_id" "suffix" {

byte_length = 4

}

resource "libvirt_volume" "disk" {

name = "${var.vm_name}-${random_id.suffix.id}.qcow2"

pool = var.pool_name

base_volume_id = var.image_id

format = "qcow2"

}

resource "libvirt_domain" "client" {

name = var.vm_name

memory = var.vm_memory

vcpu = var.vm_vcpu

# cloudinit = libvirt_cloudinit_disk.vyos_cloudinit.id

disk {

volume_id = libvirt_volume.disk.id

}

network_interface {

network_id = var.wan_id

wait_for_lease = false

mac = "52:54:00:12:34:56"

addresses = ["10.0.2.15"]

}

network_interface {

network_id = var.lan_id

wait_for_lease = false

mac = "52:54:00:12:34:57"

}

boot_device {

dev = ["hd"]

}

graphics {

type = "vnc"

listen_type = "address"

autoport = "true"

}

console {

type = "pty"

target_port = 0

target_type = "serial"

}

}

resource "null_resource" "ansible" {

depends_on = [libvirt_domain.client]

provisioner "local-exec" {

interpreter = ["bash", "-c"]

command = <<-EOT

#!/bin/bash

set -e

echo "-- Executing Ansible -- "

ANSIBLE_HOST_KEY_CHECKING=False \

ansible-playbook \

-i "${path.module}/ansible/hosts.ini" \

-e "domain=${var.vm_name}" \

-e "ssh_pubkey=${split(" ", file(var.ssh_pubkey_path))[1]}" \

-e "ssh_keytype=${var.ssh_keytype}" \

"${path.module}/ansible/main.yml"

EOT

}

}

This looks like a lot initially, but reading through it is rather simple. You define a disk, from the image pool we created earlier (we’re actually passing it through as different modules and remote-states, super handy) we then create the client with a few parameters, mainly the disk, the name, the network interfaces, which we define a static ip we used earlier in the VyOS setup. And console and VNC settings so we can access it after it boots.

Then there’s a null_resource which is a way to tell terraform to “provision” an instruction. Beautiful. And in this case, our provisioner is a locally executed command and we’re running an ansible-playbook which contains all of the good things we need for setting up 3 different VLANs, dns, dhcp and routes, as well as implanting the ssh-key onto the VyOS machine since we didn’t do that initially.

IP Tables

– IP TABLE PORTION – After doing quite a bit of the above, I had this issue where I could have DNS resolution from my host-network but no other traffic out of the VM. Or a more concrete example: I could ask where google.com was, get a response but not access google.com. This confused me greatly and took a day worth of troubleshooting, even the good ol’ AI had no good lead as to what was going on. It was close though, because it suspected a firewall issue, but I never configured a firewall. Libvirtd is supposed to handle creation of ip table routes so I had no idea that I needed to do this and in fact, only after troubleshooting did I realize how much of the process is still being hand-held for me. In any case, the routes to the newly created networks were not being created. So I had to manually create them in iptables

iptables is a very simple controller. I haven’t had the need to touch it and when your network works just fine, you typically don’t even want to touch it, incase you break something. However now I had to properly learn it. There’s two tables: - nat - filter

In the nat table I had to allow masquerading of the VM’s ip range. Masquerading is basically the router packaging your ip into a readable address for the internet, since your local ip is only known to your network. That’s why you can share 192.168.1.1 all you want, but you don’t want to share the IP from whatsmyip.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

*nat

:PREROUTING ACCEPT [46120:2707555]

:INPUT ACCEPT [11444:754064]

:OUTPUT ACCEPT [6939:1032648]

:POSTROUTING ACCEPT [6939:1032648]

## NEW RULES ##

# NO MASQUERADE

-A POSTROUTING -s 10.0.2.0/24 -d 224.0.0.0/24 -j RETURN

-A POSTROUTING -s 10.0.2.0/24 -d 255.255.255.255/32 -j RETURN

# MASQUERADE

-A POSTROUTING -s 10.0.2.0/24 ! -d 10.0.2.24/24 -p tcp -j MASQUERADE --to-ports 1024-65535

-A POSTROUTING -s 10.0.2.0/24 ! -d 10.0.2.24/24 -p udp -j MASQUERADE --to-ports 1024-65535

-A POSTROUTING -s 10.0.2.0/24 ! -d 10.0.2.24/24 -j MASQUERADE

COMMIT

The syntax is a bit wonky, but in short, we’re -Appending rules to to the nat table. With the -Source address of our VM’s ip range, and mapping them or excluding them to certain -Destination addresses. With certain -Protocols and the rule has a certain -Job to do.

So for the first portion we’re not masquerading any VM traffic that has a multicast or broadcast address block, since those would be used locally (it’s why we’re just returning) The second part we’re actively masquerading the rest of the ip-range. Any packet that has the source of the VM range, and the destination is anywhere that is NOT in the same network, we masquerade. (the ! before the -d)

Now for the filter table:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

*filter

:INPUT ACCEPT [2298596:5958402788]

:FORWARD DROP [34676:1953491]

:OUTPUT ACCEPT [840636:2346041122]

## NEW RULES ##

-A FORWARD -d 10.0.2.0/24 -o virbr1 -m conntrack --ctstate RELATED,ESTABLISHED -j ACCEPT

# Allow outbound traffic from the private subnet.

-A FORWARD -s 10.0.2.0/24 -i virbr1 -j ACCEPT

# Allow traffic between virtual machines.

-A FORWARD -i virbr1 -o virbr1 -j ACCEPT

# Reject everything else.

-A FORWARD -i virbr1 -j REJECT --reject-with icmp-port-unreachable

-A FORWARD -o virbr1 -j REJECT --reject-with icmp-port-unreachable

COMMIT

This is slightly different, but except we’re explicity telling our host to say any packets destined for our VM network, we want the -Output to destination to be the vibr1 interface And then we add some strictness with the -Module of conntrack, which lets us inspect the –ConnectionState. Only allowing ones that are related or established.

Then we allow outbound where the source is our VM and the -Input interface is virbr1. Allowing outbound traffic. And the rest may be pretty clear with the comments.

That was fun, and that’s some stuff that is typically done for you, like Docker for instance, if you look at your iptables rules, it’s filled with some Docker routes to make everything work correctly. And after I did that, my connections actually worked as expected. It is still curious how DNS responses still got forwarded and weren’t dropped.

Cloud-init provisioning

With the VyOS up and running the next step is the cloud-init images of Ubuntu and Fedora. This would look drastically similar to the vyos section, however we’re adding in a new section, since these are cloud images:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

resource "libvirt_cloudinit_disk" "cloudinit" {

name = "${var.vm_name}-${random_id.suffix.id}.iso"

pool = var.pool_name

user_data = templatefile("${path.module}/init_templates/user_data.yml", {

vm_hostname = var.vm_name

lab_user = var.user

ssh_pub = file(var.ssh_pubkey_path)

})

network_config = templatefile("${path.module}/init_templates/network_cfg.yml", {

})

}

We get to define the cloudinit data get gets created, the user_data, and network_config. And we can pass in a template and have variables passed in which is exceptionally useful.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

#user-data

users:

- name: ${lab_user}

passwd: $6$FK3b6.eNoOwNb7sO$EDXO3DIg0bkjUBrVpta0kXhzIz6LISuBcEOkDVmMbnyolNUZRG9j/b2KZIcW56lZrBa9lwM9OFRaRXUOPCxPr/

sudo: ALL=(ALL) NOPASSWD:ALL

ssh_authorized_keys:

- "${ssh_pub}"

runcmd:

- sudo hostnamectl set-hostname ${vm_name}

#network-cfg

version: 2

renderer: networkd

ethernets:

ens3:

dhcp4: no

dhcp6: no

vlans:

eth0.20:

id: 20

link: ens3

dhcp4: yes

And that gives us some initial configuration, setting up a user, ssh keys, the hostname and the vlan network.

SSH Ansible problems

Now the last part which is essentially the ansible playbook which allows for the complete setup of the Wazuh server, indexer, and dashboard. The construction of that was a little annoying, but surprisingly the most annoying aspect was getting the wait_for_connection aspect to work. If you’re connecting to a typical remote host it works just fine, but we’re using a bastion host which means we’re jumping off another host and that makes the wait_for_connection with ProxyJumps, not behave correctly. So what I did as…a proxy.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

- name: Wait for ssh with retries

shell: |

for i in {1..30}; do

ssh -o ConnectTimeout=5 "echo success" && break

sleep 10

done

And that managed to actually wait for the VM to boot, without terraform erroring out consistently.

I’m not going to run through the templates and rest of the roles, as it is essentially the wazuh-server setup. However there’s some fun limitations that I found having to run through it and that was disk-space. I had provisioned the VM assuming 20GB might have been enough, which it installed everything fine but initialization caused an issue. So ensure a safe 50G for space

This was a small coverage of my exploration with the homelab, I didn’t touch on the consistent refactoring of my terraform files, going from one monolith to multiple modules deployed as workspaces using remote states, but that was probably my favorite discovery not having to one-shot deployments. But it was a very enlightening experience.